Side effects in React-Redux

The default model for Redux-like architectures doesn't have a good mechanism to deal with side-effectful actions (e.g. API calls, I/O operations). Because of this, these architectures are often "enhanced" to include processes that can detect and perform side-effectful actions, then return the results to Redux.

This document takes a cursory look at the concepts that lead to these enhancements and briefly touches on two practical implementations and their broad tradeoffs: redux-thunk and redux-saga.

Structure and determinism

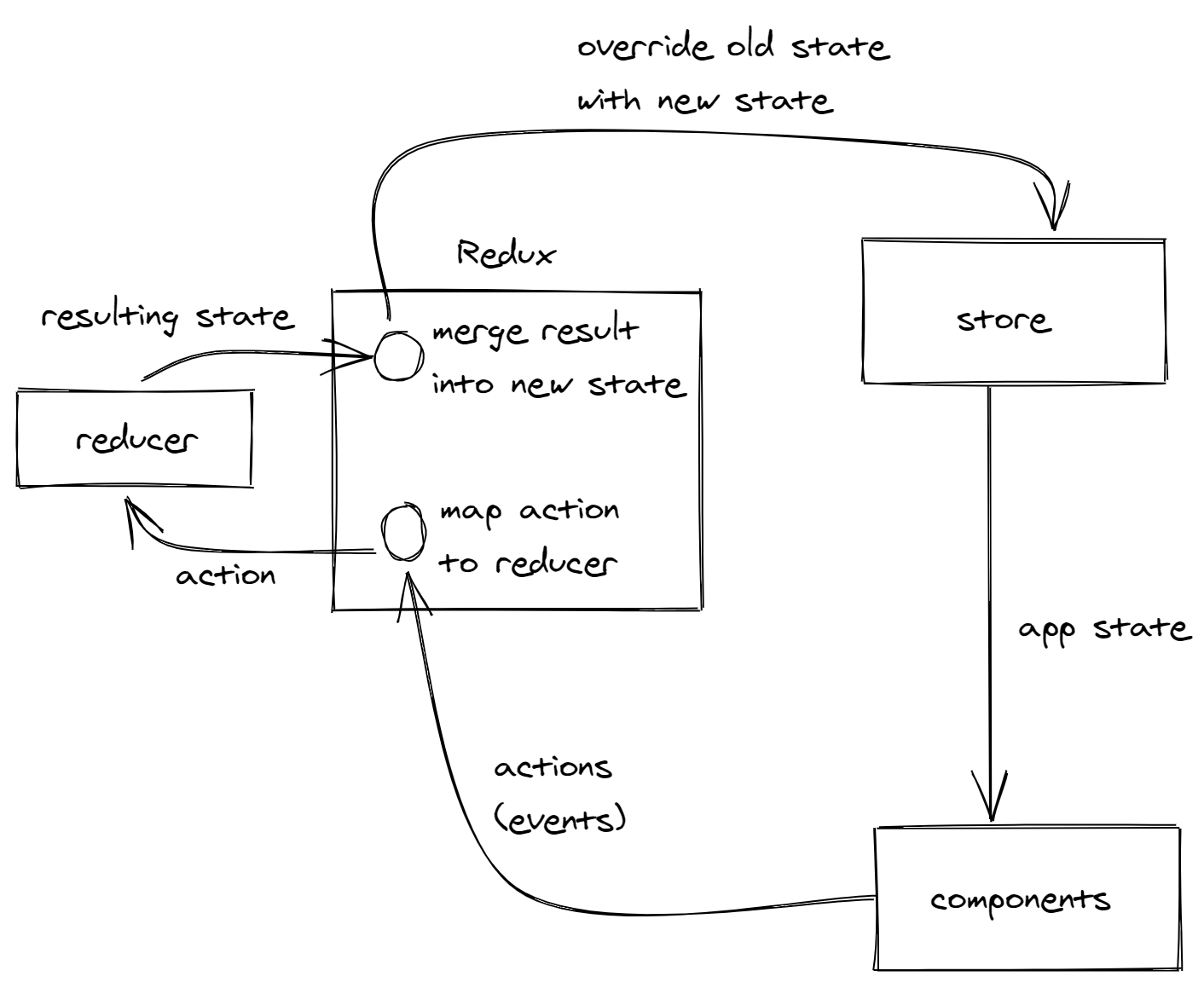

Redux apps broadly have the following structure:

- A central store holds the state of the application. This state is propagated through to the application's components.

- Components make up the view/output of the app and configure/render themselves according to that state i.e. they are driven by the state.

- Components emit actions (events) when the guests of the app interact with them. These actions can also carry payloads e.g. an action for user input can have the input string as a payload.

- Actions are observed by Redux and mapped to reducer functions. The reducer functions process the actions (and their payloads) and determine what the new state for the application should be.

- The resulting state is given back to Redux, which merges it into the central store.

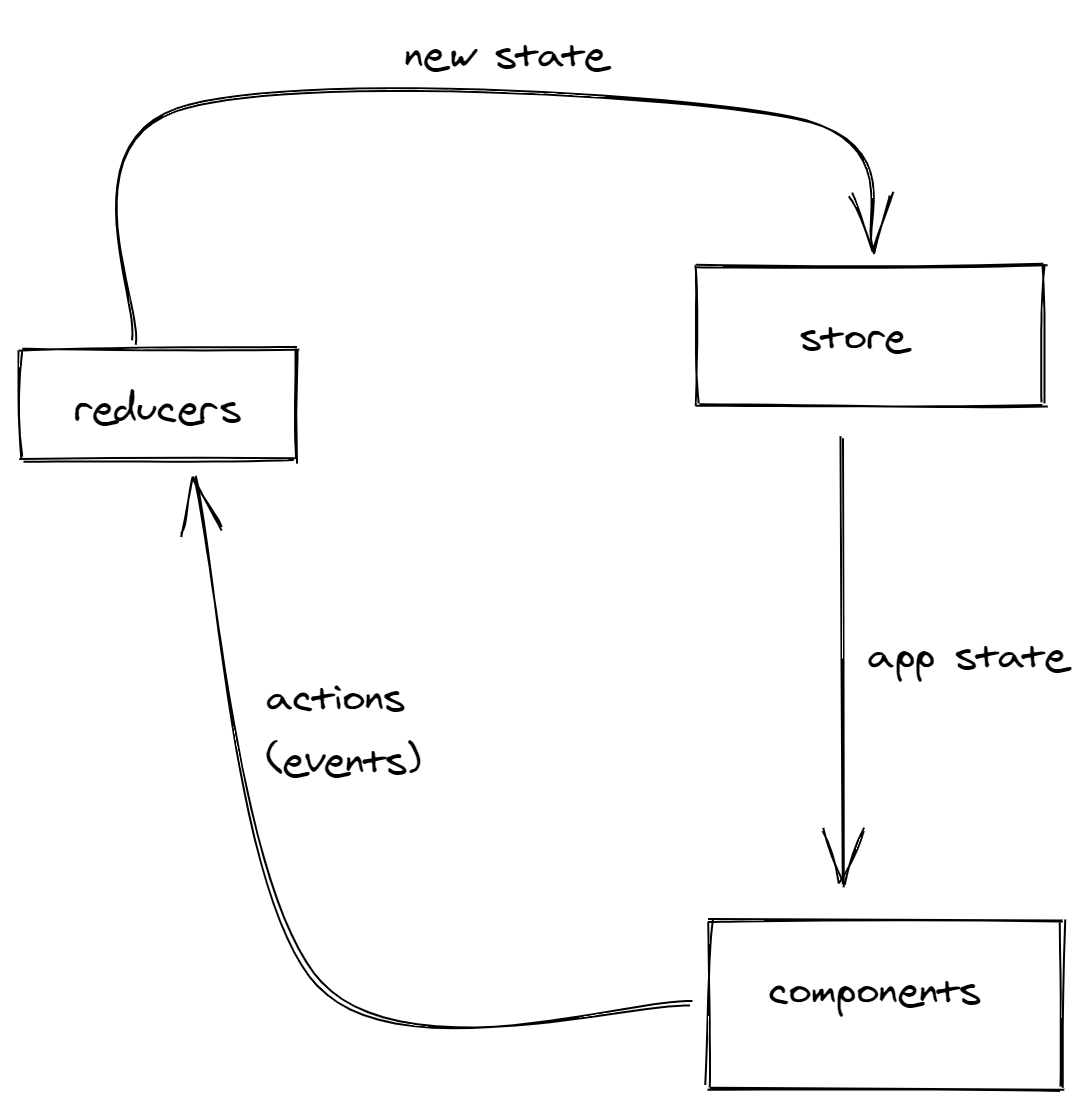

For this discussion, we can simplify this conceptual model to drop the internal Redux bits.

The central advantage of this structure is that our app can be deterministic: you can be sure of how the application will behave if it's in a certain state. This property is the principal motivation behind Redux i.e. if we lost this property, we practically drop the primary advantage of using Redux.

To keep this determinism, however, requires several conditions which make it difficult to take side-effectful actions:

- The flow of data from the store to the components needs to be side-effectless - this is necessary to ensure that the application will behave deterministically for a given state.

- The actions emitted from the component are pure objects; there's no opportunity to run a side-effectful process as it currently is.

- The reducer functions themselves also need to be side-effectless for the actions to be deterministic i.e. the result of a reducer will always be the same for a given action and payload.

That doesn't leave much space for us to perform side-effects within Redux's structure.

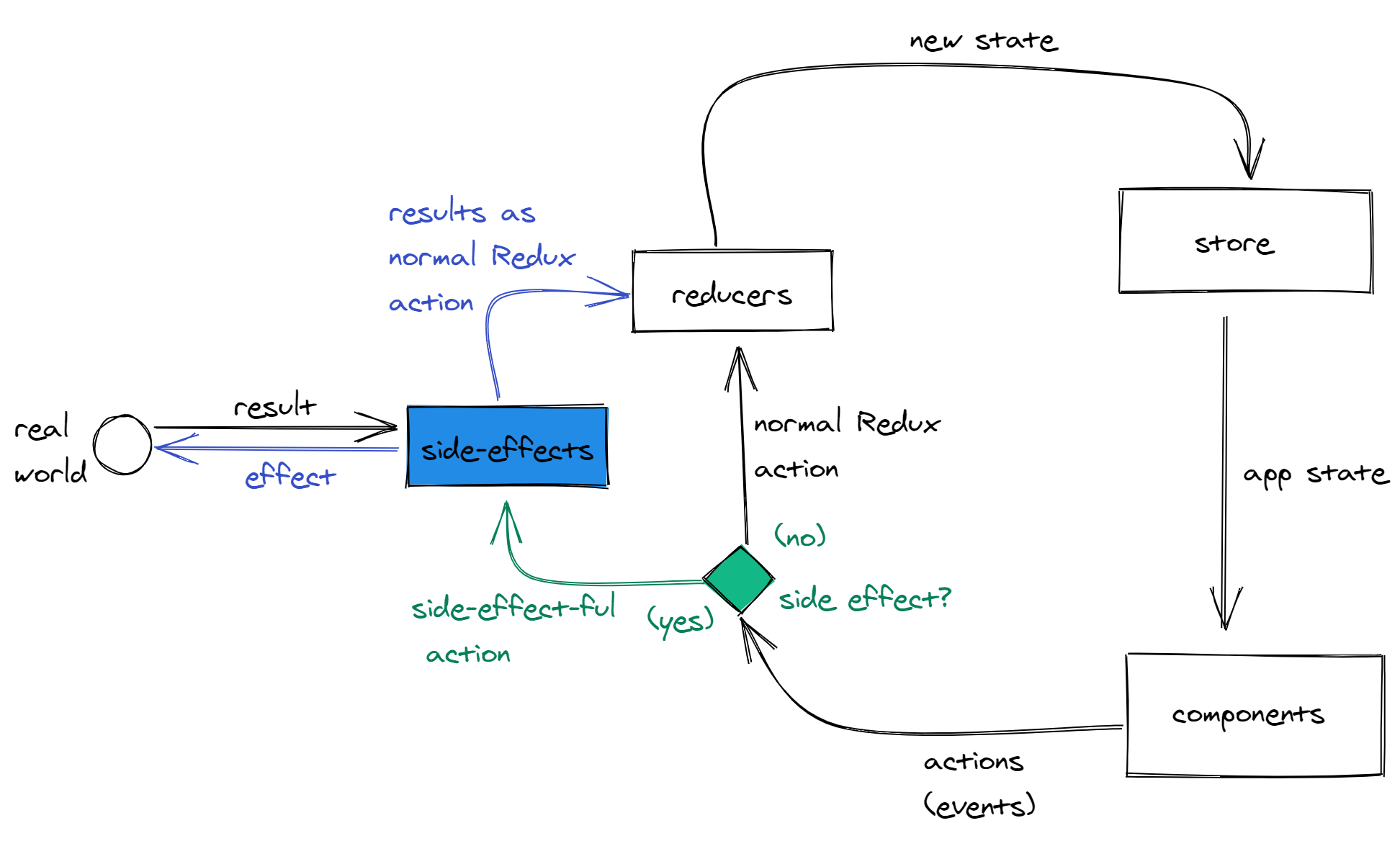

Creating a space for side-effects

If we can't work with side-effects within Redux's structure then what if we drive side-effects outside/independent of Redux? This idea is central to the mechanisms we'll be diving into here.

At a conceptual level, we need three things to make this happen:

- Processes that can run independently of Redux. This is the biggest difference between implementations; we'll discuss ways to do this when we discuss

redux-thunkandredux-saga. - A way to trigger these processes from within the Redux app. We already have the concept of actions that components can dispatch that we could expand on i.e. we can define a new type of action that can specifically trigger side-effectful processes.

- A way to feed the results of the processes back into the app. One relatively simple solution for this (and the one we'll assume here) is to use normal Redux actions to deliver the payload back to our app.

Implementations of side-effectful structures

In this section, we'll look at redux-thunk and redux-saga which are (at the time of writing in 2021-02) two libraries that enhance Redux to enable side effects based on the model we discussed above. Both of them make use of Redux middleware to hook into Redux and define when processes should happen within Redux and when they can happen independently.

For both implementations, I'll also provide some of my thoughts around their benefits and drawbacks. These reflect my thoughts at this snapshot in time and are based on my own experience with working with these libraries. I suggest you run your experiments with these libraries to vet whether these thoughts also apply to your context/systems.

redux-thunk

redux-thunk allows components can dispatch functions similarly to how they dispatch actions.

Doing this allows side-effectful actions to be differentiated from normal ones (typeof action === "function" ? sideEffect : normalAction) and sets up a way to run a process outside of Redux (by just running the function itself).

With this approach, the components are aware of the functions, which they dispatch and those functions execute immediately upon dispatch.

This has some useful properties:

- The approach is incredibly simple and lightweight (it's a total of 14loc). This has benefits when you're trying to debug as you don't need to try to debug what the middleware is doing.

- It's intuitive/quick to learn. "You want a function to run? Just dispatch it"

- Next-to-no extra boiler-plate code. After setting up the middleware you can immediately start dispatching functions.

However, coupling components and the functions they need to dispatch has several implications:

- It's not straightforward to re-use a component in another context/service where the same action needs to trigger a different function e.g. fetching data in one system may require an API call whereas another system may need to read the data from disk.

- This blurs the separation of concerns between components and functionality. In pure Redux, components take in state and emit interactions. In this model, they also essentially control side-effectful flows. This added concern can lead to "heavy" components if it needs to perform multiple side-effects.

- The component emitting side-effectful functions can also increase the complexity of testing that component. Side-effects often need to be mocked/stubbed, so the component needs to be written in a way that makes this mocking possible within tests.

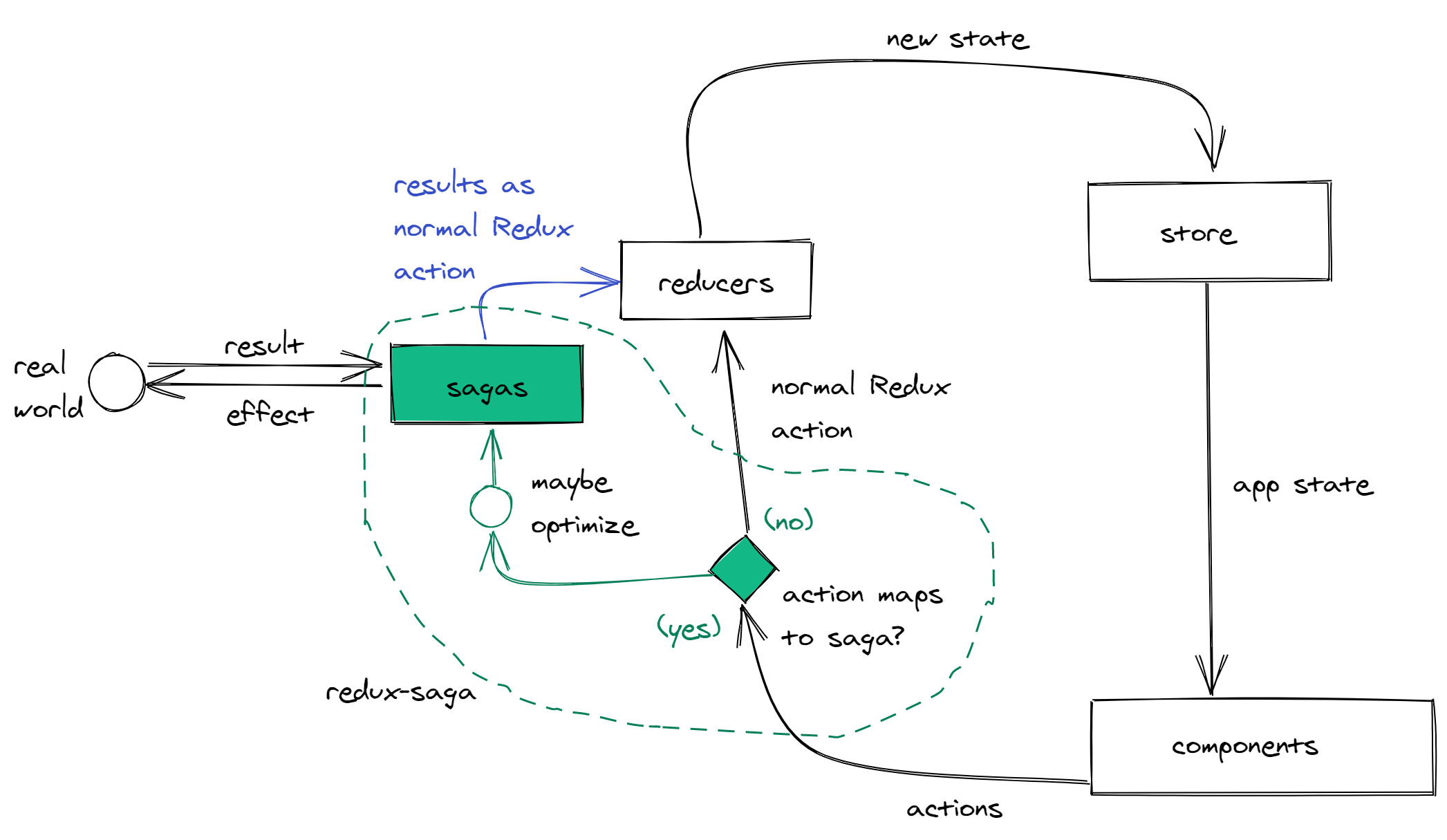

redux-saga

On a simplified level redux-saga sets up listeners for normal (aka. Redux-like) actions that you define. When an appropriate action is caught, the listeners trigger functions (technically they're function generators) called "sagas" that define the potentially side-effectful code you want to run for that action.

With this approach, the components only know about actions. The sagas and the mapping between actions and sagas are set up when redux-saga is set up, which is independent of the component.

Benefits of this approach:

- Components can be kept simple. All the added complexity of side-effects is encapsulated in sagas. This is useful for code reuse as a component can be re-used in a different context where its actions are mapped to other sagas.

- redux-saga can decide when to run a saga. This allows it to provide optimizations e.g. only run a saga for the latest action rather than for every action. This can save a lot of time/prevent bugs if you were to implement this yourself.

- Sagas and components can be tested independently; components tests can focus on testing that the correct actions are dispatched. This separation of concerns can allow you to have simple component tests (which are expensive relative to normal unit tests); not having side effects in components means you don't have to re-render the component and account for potentially asynchronous logic. Alongside this, the trickier side-effectful logic can be tested using normal javascript unit tests.

Downsides of this approach:

- redux-saga has multiple responsibilities of deciding what to run and when to run it. This makes it much a heavier middleware relative to redux-thunk.

- You need to set up mappings between actions and sagas as well as set up optimizations. This can lead to a fair bit of boilerplate code.

- It isn't conceptually obvious. How to set up new sagas and how to work with them can take some time to learn. The use of function generators can also trip up some engineers; it is a JavaScript feature that's usually considered advanced.

- It's easy to create a complicated system using sagas. Nesting sagas (sagas that call other sagas), complicated mappings between actions and sagas, and impulsive use of optimizations can quickly lead to a system that's difficult to understand and debug.